The Most Bizarre Jihadist Trial You’ve Never Heard Of

Originally published on Beaconreader.com, November 4, 2013.

In January, 2014 the ACLU filed a lawsuit on behalf of Jamshid Mukhtarov. They are bringing their suit because Mukhtarov may have been directly surveilled by the NSA — and they think it was unconstitutional to have done so. I wrote, when this was first revealed publicly last November, that it was troubling to see why his case, which was so odd from the start, was getting attention only now. That still troubles me.

Jamshid Mukhtarov started out as a campaigner for human rights in Uzbekistan, but was arrested in the U.S. last year for materially supporting a banned terror group. His case is a petri dish of what’s wrong with America’s war on terrorism.

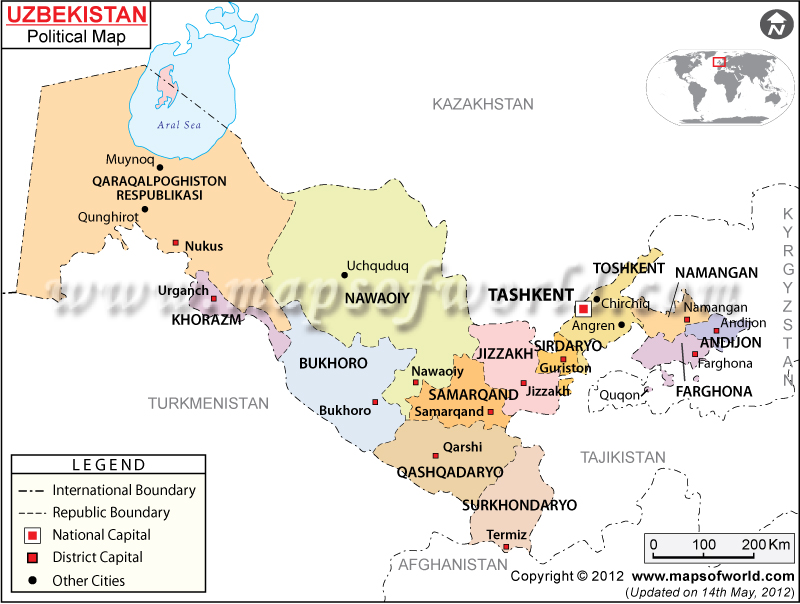

Jamshid Mukhtarov started out his public life campaigning for human rights in Uzbekistan. After the horrifying massacre in Andijon, where hundreds of protesters were gunned down by government troops, Mukhtarov fled to Kyrgyzstan, and eventually as a refugee to Denver, Colorado where he worked as a truck driver. Yet now he’s on trial for providing material support to a banned terrorist organization. His case, and its many bizarre twists and turns, is a perfect storm of how the legal side of the war on terrorism is developing cracks people can slip through.

Mukhtarov used to be aprominent figure in the Ezgulik Human Rights Society, based in Jizzakh. According to Ferghana News, he faced harassment from the Uzbek government because of his activism.

“Human rights activists and oppositionists giving the population of Dzhizak the alternative information on the tragic events in Andizhan this May are being suppressed and harassed,” Dzhamshid Mukhtarov of Human Rights Society Ezgulik told foreign journalists on December 22 [2005]. According to the activist, 15 representatives of the human rights community were assailed and beaten and threatened with displacement in Dzhizak itself and its environs.

Mukhtarov himself barely avoided arrest on fabricated charges of being an Islamic fundamentalist in August 2005. He avoided detention only because Birlik leader Vasila Inoyatova phoned the then Interior Minister Zakir Almatov on his behalf. Mukhtarov’s activeness in the human rights movement rekindled his conflict with law enforcement agencies.

Keep the name Vasila Inoyatova in mind for later. She was instrumental in helping Mukhtarov fend off fabricated accusations, provided by the Uzbek government, that he was an Islamist. At least at the time, he was not. David Walther, who was living in Uzbekistan, described how unusual the charge of Islamism was:

Another very interesting nugget that comes out of these stories, though, is that in Dzhizak in particular (I don’t necessarliy recall seeing this in other regions) these human rights activists, when they are arrested, are rung up on charges of “islamic extremism” rather than the more sophisticated (but equally vague) financial charges that Tashkent authorities like to use. The Dzhizak authorities seem consistently more exhuberant about enforcing and maintaining the party line (along with an enthusiastic strain of America-bashing) and less concerned about being openly corrupt than their Tashkent peers.

It’s entirely possible that Mukhtarov had contacts with Islamist groups operating in Uzbekistan — there is, at times, some overlap between legitimate political opposition to the abusive regime of Islom Karimov and the Islamists trying to unseat him. At the same time, the Karimov regime trumps up the Islamist terror hype to justify crackdowns on political dissidents, even when they have no connection to those groups.

One clue about Mukhtarov’s affiliations during that time is a leaked State Department Cable from the U.S. embassy in Tashkent in 2006. Jamshid has just taken over leadership of the Jizzakh branch of Ezgulik, the human rights organization. It is in disarray. Vasila Inoyatova, who had previously advocated on behalf of Jamshid Mukhtarov, was complaining Mukhtarov was not doing his job properly. After months of arguing about finances and leadership (he believed Inoyatova was “too reluctant to mount open demonstrations and protest publicly against the government,” according to the cable), Mukhtarov broke with Inoyatova to join with a rival political party.

That rival political party got Mukhtarov into trouble. Though it is called the Free Farmer’s Party and Mukhtarov had been campaigning on behalf of farmers who need help defending themselves from corrupt government officials, it was also openly calling for regime change in Uzbekistan. Karimov, the dictator, does not look kindly on such advocacy. In 2006 Mukhtarov was caught pamphlets from Human Rights Watch literature about the Andijon massacre, and was soon under house arrest over “sexual harassment” charges. As before, with the accusation that was an Islamist, those charges were without merit.

Mukhtarov was quickly smuggled over the border to Osh, Kyrgyzstan. There, too, Mukhtarov faced harassment from the Uzbek security services. According to a July, 2006 report on the Kyrgyz news site 24.kg, Mukhtarov said he faced the threat of death if he did not leave “within three days.”

By that time, the U.S. had begun processing asylum requests for Uzbeks who had fled the Andijon massacre. At some point — it still unclear exactly when — Mukhtarov and his family came to the United States as asylees.

It was here, in the U.S., that federal prosecutors allege Mukhtarov became radicalized and began to communicate with terrorist organizations. In the photo above, scrounged up by Radio Ozodlik, Mukhtarov is sporting a beard many think is a sign of adopting Islamism. It is certainly a dramatic change from the man at the top of this post, who did not have such facial hair. It also might be meaningless. Sometimes a beard is just a beard.

In the affidavit for his arrest in January of last year, the government accused Mukhtarov of working with the Islamic Jihad Union, a sort of splinter-group of Uzbek militants hiding out in northwest Pakistan. The IJU is well-known to U.S. intelligence for its brazen attacks in Afghanistan. “They are pretty hardcore,” says Noah Tucker, the managing editor of the Central Asia blog Registan.net and an expert on Uzbekistan. “They want to be the Uzbek al Qaeda.”

The FBI gleaned this information by monitoring his emails with the administrator of Sodiqlar.com (now Sodiqlar.info), the website used by the IJU to advertise its activities. In that email, Mukhtarov reportedly said he was planning to attend a “wedding,” which the FBI interpreted as being code for a suicide bombing. Mukhtarov also reportedly indirectly referred to IJU militants as “our guys over there,” and had a fight with his wife about a trip to Turkey. When he eventually bought a ticket to Istanbul, the FBI decided to grab him at the airport.

All things being equal, the public evidence in government affidavits against Mukhtarov is pretty thin: it amounts to exchanging emails with the website admin of a terror group, having some coded phone calls, and buying a plane ticket. He is not accused of trying to bomb anything or kill anyone, just “materially supporting” the IJU though providing either himself or by carrying to them a some cash he was reportedly arrested with.

It is the point of Mukhtarov’s arrest that his plight becomes truly bizarre. He fled his home because a repressive government would not permit him to advocate on behalf of farmers, then threatened him with death for organizing human rights activists in a neighboring country. His opposition to the Karimov regime is without question — he’s been open about it. But what seems odd is how all of the talk from prosecutors of his “joining” the IJU is just that: talk.

When he was first arrested, in January of 2012, officials said he was “working with the IJU,” and even hinted that he was planning to fight overseas (though at first they would not say where). They were explicit, in talking to reporters, that he had no plans to do anything inside the U.S.

Yet in a hearing about his case, the prosecutor employed secret witnesses — whose identities were kept secret for national security reasons — to implicate Mukhtarov in the global jihad, something the public record about him, and the public evidence released in the affidavit, did not support. The prosecutor tried to connect Mukhtarov to both Osama bin Laden and Anwar al-Awlaki, but did not provide any direct evidence for the claim.

It is possible Mukhtarov fell afoul of America’s loosely-worded material support laws, which can criminalize even communication with banned groups. But that doesn’t make him a terrorist, as opposed to merely unlucky.

Yet in the nearly two years Mukhtarov’s arrest, his plight had gone largely unnoticed by the public until last month, when the government gave official notice it was going to use NSA-collected information to prosecute Mukhtarov. In doing so, they levied a new accusation to journalists, claiming he was going to travel to fight for al Qaeda in Syria — something the IJU, as best as anybody can determine, has never done (they fight exclusively in eastern Afghanistan and northwest Pakistan).

I reached out to Mukhtarov’s lawyer about the new claims. “Mr. Muhtorov’s indictment has not been expanded to include going to Syria,” she responded by email. She also said that he “never was facing” the charge of attempting to travel to Afghanistan, despite the repeated invocations of Afghanistan in the initial official discussion about his case.

It’s not clear why the federal government is accusing Mukhtarov of traveling to different, changing conflicts in public but not adding these charges to his indictment. J.M. Berger, a researcher who studies extremism, looked at two superceding indictments and was puzzled. “The volume of documents restricted or redacted in this case is extremely unusual,” he said, as is “the relative absence of unredacted documents.”

Moreover, none of the public documents about Mukhtarov and his indictments mention Syria. Nor do any of his hearing transcripts or public statements by officials until last month. It’s unclear where, how, or when Syria suddenly entered the picture.

It’s possible all of the redaction and inconsistencies is because of those NSA intercepts that will now be a part of Mukhtarov’s case. That would make his case historically significant, as the first terrorism case involving NSA collection. But many questions about Mukhtarov’s case remain.

The first is what, exactly, Mukhtarov has done? There remain in the public record no indication that he actually planned to join the IJU to fight overseas. He seems to have communicated with an IJU website administrator and bought a plane ticket to Turkey, but that on its own is not evidence of planning to wage jihad (even if Turkey is a major hub for fighters traveling into Syria). While it’s true that the material support laws might warrant a prosecution here, so far there’s been nothing released that moved beyond what amounts to a thought crime: essentially, talking big on the internet and boasting over the phone.

The second is what else might be driving this case? There is a chance that Mukhtarov is being pressured to give up more information about Bakhtiyor Jumaev, another Uzbek national living in the U.S. who is accused of providing material support to the IJU. Mukhtarov is named in the criminal complaint against Jumaev, though in Jumaev’s case the public evidence is just as frustratingly vague and circumstantial as it is for Mukhtarov.

There is an additional chance that Mukhtarov is being pressured to provide information about Fazliddin Kurbanov, who was arrested in May on charges of both material support for an Uzbek terror group (this time the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan, or IMU) and “unregistered destructive devices.” An additional indictment filed by a grand jury in Salt Lake City charged Kurbanov with “distribution of information relating to explosives, destructive devices and weapons of mass destruction” (which is the legal definition of a bomb).

According to Kurbanov’s brother, Fazliddin had traveled to the U.S. as a refugee from Tashkent, Uzbekistan’s capital. A mutual friend advised Fazluddin to travel to Denver, where he reportedly became friends with Jamshid Mukhtarov and joined his truck driving business.

There’s one hole in these theories: they’re not based on anything real. Fazliddin’s indictment starts its timeline in August, 2012, eight months after Mukhtarov was arrested. If there is a Mukhtarov connection, it’s coming after the fact. There’s equally unclear evidence pegging Jumaev to terrorism — he is accused of sending Mukhtarov $300 for that wedding prosecutors insist is terrorism and for posting some pro-IJU comments to a YouTube video. The indictment didn’t say what the $300 was to be used for, nor does it say how that money would aid the IJU. It is difficult to see how that is really a crime.

It is possible that the NSA-derived collection fills in the picture a bit more. In fact, it is possible that NSA evidence was that secret “witness” the prosecutor at Mukhtarov’s first hearing mentioned. But even there, it’s unclear what it could be: Prosecutors have already said they had court orders to listen to Mukhtarov’s phone calls and read his emails, and in their public indictment used that evidence to justify accusing him of violating material support laws. What else would the NSA add — is that where they got evidence he planned to go to Syria?

But if that’s the case, why would officials have told media last year — erroneously, it should be noted — that Mukhtarov had planned to fight U.S. forces in Afghanistan? That was a recurring theme of the media coverage of his arrest and initial indictment, but now that’s gone, replaced by talk of Syria — where the IJU has never been known to operate.

Worse still, it seems the prosecution had relied on random blogposts to try to cast doubt on whether Mukhtarov was really a human rights activist. In describing Mukhtarov as too violent to release, it appears the prosecution tried to say he had faked his experience as a human rights worker in Uzbekistan:

A prosecutor also asserts that Muhtorov may have misrepresented himself a human-rights activist and that he may have received refugee status on fake grounds…

Holloway writes that some online articles say Muhtorov was an “opportunist who was dismissed from the Ezgulik Human Rights Society because he supported violent extremism.”

Another, Holloway wrote, “claims the defendant acted as an informant for Uzbek intelligence and received refugee status on fake grounds.”

Those articles come from Catherine Fitzpatrick, who is active in online circles and has a history of personally attacking those she disagrees with. She has spent, without exaggeration, years trying to personally defame a number of scholars, journalists, and activists who do not share her political beliefs, including this writer, and took to her blog to then try to defame Mukhtarov because people she disliked had expressed skepticism of his case (that full story is here).

That is who the prosecution relied on to try to deny Mukhtarov’s well-documented history with personally risky human rights activism in Uzbekistan. It was astonishing to long-term watchers of the country.

It is hard not to see Jamshid Mukhtarov as the victim of bad luck. Last May he held a brief hunger strike to protest his austere conditions. He also may have broken U.S. material support laws about banned terrorist groups.

The problem, however, is with those laws, which seem to have criminalized speech, even thought. Until last month, Mukhtarov was not publicly accused of wanting to do anything beyond support a terrorist group — and he is still not officially accused of wanting to fight (that’s a line officials have given reporters even though it never appears in his indictment).

There is a legitimate and genuine threat from Uzbek terror groups, including both the IJU and IMU. But it is difficult to see how those groups are successfully countered by criminalizing speech and persecuting human rights workers for their associations online.

These men have fallen through the cracks of the war on terror and are being profoundly punished for their thoughts, associations, and travel patterns. This is, essentially, pre-crime — accusing people of terrorism when they’ve done nothing but say some bombastic things in a gmail conversation or phone call.

Before the U.S. government admitted it had used NSA intelligence in Mukhtarov’s prosecution, his case had faded into the background, just another foreign name being accused of terrorism that no one paid attention to outside of a tiny community of Central Asia analysts. Now, his case if grabbing higher-level attention, and there is a chance it will rise to the Supreme Court over a challenge about the legal validity of using foreign intelligence collected without a warrant to prosecute an asylee living in the U.S. All of the loosely defined and collected evidence, poorly-worded laws, and guilt-by-association by the FBI hasn’t been enough to rally civil liberties advocates on Mukhtarov’s behalf; but the involvement of the NSA is.

There is probably another message in there, but it’s too depressing to think about.