The Missing Gap of Context

Followers of me on Twitter know I’m not a fan of some new types of journalism currently clogging the intertubes. I’ve been pretty up front about how I think “explanatory journalism” is more often neither, and that the reliance on animated GIFs to either make a point or a joke is meaningless and distracting when it’s not actively offensive by trivializing war and death.

The problem is, the worst aspects of both explanatory journalism and GIF-based “writing” are not limited to the standard bearers of the genre: Vox, 538, Buzzfeed, et. al. Rather, the bad habits those sites encourage, both through their generous venture funding, extremely high profiles, and in Buzzfeed’s case runaway profitability, are spreading. Now, normal news services and even blogs that once were constrained in how they would cover topics will cop to posting pictures and lists of things without any context or explanation whatsoever. The net result, it should go without saying, it to barrage readers with neat things that, ultimately, have no meaning to them.

Take io9, one of my absolute favorite daily reads, which covers science, speculative science, science fiction, and (some) cutting edge technology. They’re fantastic, I loved Annalee Newitz’s book on the future of humanity, and by and large the writing there is fantastic and thought-provoking (and really good for writers, too!).

However. That’s not true for everything. Last night, io9 ran a post about the architecture of Astana, the capital of Kazakhstan (above is a photo I took of Congress Hall in Astana in 2003). And while the buildings published are indeed striking visually, there is zero information on where those buildings came from (apart from the western architecture firm hired to design them), how much they cost, or even in some cases what they do. It is, literally, just voyeurism at some weird buildings.

This might not matter if all you care about is saying “oooh, pretty building.” But knowing a bit about Kazakhstan, as a place, gives all of those bizarre “post-Soviet” designs (how post-Soviet are they if Westerners design and build them?) a very different perspective.

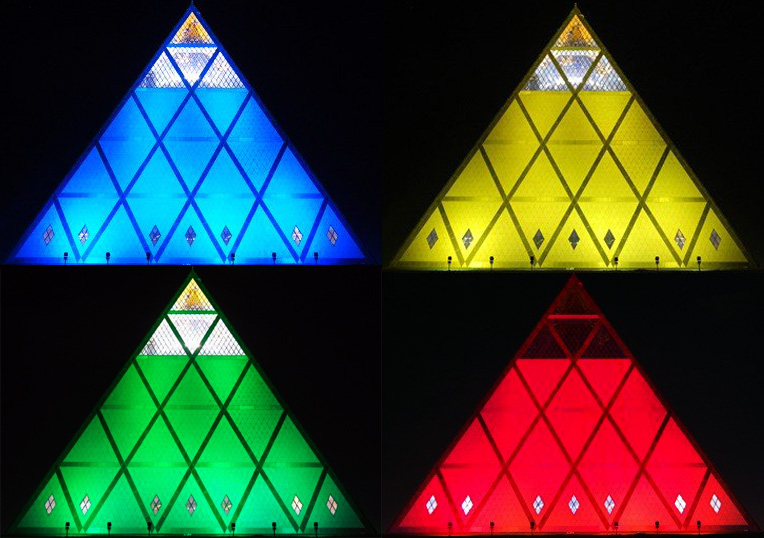

For example, take one of the most often photographed artifacts, the Palace of Peace and Reconciliation. A gigantic, 62-story high pyramid of glass designed by Norman Foster at a cost of around $60 million in 2006. Just three years previously, when I was there, Astana was a barren, depressing, wind-swept nothing of a small town: no culture, no transport links (I had to travel there from Karaganda, where I was living at the time, on a rickety old train), and little to do except drink to excess. In fact, no one really seems to know why president-for-life Nursultan Nazarbayev moved his capital from the picturesque, cosmopolitan city of Almaty (pop. about 1.5m) to a barren town of, at the time, about 200,000. Before Nazarbayev moved the capital north in 1997, Astana was more famous for hosting one of the most notoriously cruel Soviet gulags.

As Joshua Kucera wrote several years ago, “perhaps the must fundamental question is why it exists at all.” Sure, Astana was less prone to earthquakes than Almaty, and sure it’s a tiny bit more centralized than Almaty (way down on the southeastern fringe of the country). But also, Astana is in the middle of a large Russian minority population, leftover from the collapse of the USSR, and some Kazakhs feared, early in their independence, that those Russians could form a sort-of fifth column in the country if they remained distant from the central government (an eerily prescient view considering what’s going on in Ukraine). But really, there was little reason for it other than ego: that’s why Nazarbayev takes personal charge of so much of the architecture design, and it’s why his officials take extra care to brag about the glories of the new Kazakh architecture.

It’s difficult to square Nazarbayev’s desire for a glorious capital city with the country’s growing inequality. Indeed, even as the country has swelled with oil wealth — the source of financing for all of those very expensive “strange, post-Soviet” buildings — that windfall has benefitted very few people. While Kazakhstan’s overall per-capita GDP is around $12,000, making it an upper-middle income nation, there is a growing wave of discontent at how much wealth the elites are capturing. In 2011, that spilled over into mass riots in the western oil town of Zhanaozen, where a government crackdown resulted in at least 15, and quite probably more, unarmed people being gunned down by heavily armored riot police. Meanwhile, in almost every indicator available to research, civil liberties in the country are disappearing — speech is being suppressed, dissent criminalized, newspapers shut down, and opposition political figures imprisoned. It is a dramatic, sharp turnaround for a country that just a decade ago seemed to be liberalizing little by little.

All the while, though, Kazakhstan revels in world media attention for its role in the P6-Iran nuclear talks, and of course blog posts like io9’s about what pretty buildings its unelected president is building in the capital. It’s not called a “gilded cage” for nothing — despite the glitz and Las Vegas-like kitsch of Astana, from a social and political perspective the country is measurably worse off than any time in the 21st century.

That is why, when I see context-free blogposts about what neat buildings Astana has, I get a bit of a pit in my stomach. While the internet ooohs and aahhhs about how wonderful the buildings are, attention is drawn away from the very real, and very upsetting, change taking place in that country — one I continue to love and miss ever since leaving eleven years ago. Just look at the readers’ reaction — all dazzled by the supposed glamor of such monumentalism, with nary a thought for what Kazakhstan is actually like, because pictures of a building convey almost no meaning without context.

Now, io9 has written stirringly in defense of using GIFs in science writing before, and they are right: when an image or a GIF helps explain a story it’s a wonderful thing! But just posting images from what can only be called a dictatorship, without even any discussion of the science that went in to creating such progressive building shapes, it little more than voyeurism. And while that’s fine for a personal tumblr or something, there’s no real value to a science blog (or almost any publication worth taking seriously) gawking at the silly things foreigns build far away.

(An aside: at least in another context at io9, I can see I’m not the only one lamenting the inexorable rise of clickbait headlines & editing practices derailing otherwise usable content)