A Red Mars Revival

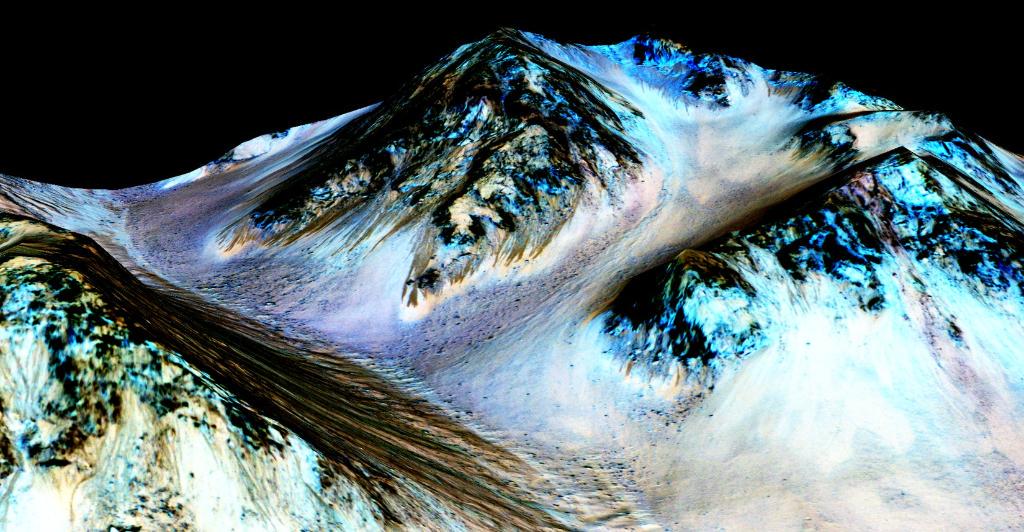

Let us celebrate with amazement the discovery of liquid water — of a sort — on Mars!

This is a dream come true for so many who want to build a colony on the Red Planet. And indeed, the idea of water — even water with so much perchlorate in it that it becomes antifreeze — existing on the surface, apparently so close to the surface that it can be measured from space — makes is sound like we are getting ever-closer to being able to live there, permanently, sustaining our presence through what’s known as in-situ resource utilization, or ISRU.

The basics are there: Though toxic to humans if untreated, perchlorates have a lot of uses, but mostly as propellant for rockets: ammonium perchlorate is the fuel source for solid rocket. Lithium perchlorate is used in batteries. Perchlorates are also used in “oxygen candles,” which release O2 as they burn.It’s feasible, even easy, to generate water and oxygen by burning perchlorates on Mars.

So what’s the problem?

First off, there’s the law: the 1967 Outer Space Treaty prohibits NASA, or any national space agency for that matter, from approaching any extraterrestrial source of water for fear of contaminating it with our own bacteria (which may have already happened; we don’t know yet, but we do know some microbes have survived on the outside of the space station, which shouldn’t be possible but somehow is).

Secondly, making anything useful on Mars is going to cost a heinous amount of energy. In the video above, that very smart NASA scientist is describing a process by which Martian soil can be baked, and the results condensed and further processed. This requires very high temperatures — the Curiosity rover has a pyrolysis gas chromatograph mass spectrometer that heats its soil samples to more than twice the boiling point of water, which happens to decompose perchlorate and thus generate the oxygen NASA is so excited about.

Here’s the thing though: doing that in a tiny chamber to test a tiny soil sample is relatively easy. Doing it on any scale to make it viable for human use is extreme — especially if the resulting water is going to be further electrolyzed to try to make liquid rocket propellant. The amount of power would be easy to secure on earth, but on Mars it’s really hard — we cannot generate enough power from the teeny amounts of plutonium that are available for radioisotope thermal generators (NASA can make 3, and that’s it for well over a decade). Solar panels would generate enough electricity — if you had enough of them, exposed to the sun for long enough, and they weren’t being used to also power heaters and computers and lights and whatnot.

In Andy Weir’s The Martian, the return capsules have these systems set up, but they are meant to be in operation for well over a year, and that only makes enough propellant for a single, small capsule to take off. This stuff works very slowly.

The energy issue might be solved another way, however. Perchlorates can be digested by bacteria — Earth bacteria, as in not-from-Mars. We can breathe on Mars if we digest its soil with our germs. And that’s a real problem.

Humans are actually quite filthy. We walk around, at all times, with a unique, personal cloud of microbes that cover and infect everything we touch, breathe near, and encounter. But we’re also fussy: if our biological systems are disrupted by even minor amounts of certain contaminants, our bodies malfunction and shut down.

Mars, too, is a filthy place — it is like Antarctica, but worse in every way. It is freezing cold, you cannot breathe, the soil is horribly toxic for extracting drinking water or growing things without heavy processing, and the toxic dust is so atomized it can seep into any seal we can manufacture and coat its inner surface. In Antarctica when an ice storm forces snow into a building seal, it just fills up with snow — disruptive, a bit, but manageable. On Mars, such a buildup is toxic if untreated, since perchlorate even at relatively low concentrations can disrupt the thyroid (and Martian soil is heavily contaminated with perchlorates).

There might be bacteria or something on Mars already, but we’d never know: our only soil analysis tools require heating the samples so high that the release of perchlorate destroys organic carbon if any exists. So we don’t know if there is a native ecosystem in place — though if there is one we can probably assume it is very fragile. I’m sure it’s possible to generate air this way, but I’m not sure we’d really want to.

Our options for living on Mars boil down, in one case literally, to either burning the soil to make what we want, or infecting it with our germs to make what we want. This does not make living on Mars impossible by any stretch, though it does make living there monumentally difficult. But I’d like to broach another idea: should we even bother?

I’m aware of the ideology of people like Elon Musk (who wants to nuke the poles!) and Stephen Hawking, who are convinced that we must leave Earth if we are to survive as a species. But I am actually much more persuaded by Kim Stanley Robinson’s philosophy, which has evolved over time to include some idea that there is something unique to our planet that we simply cannot escape or escort — at any rate, not while still remaining genetically unmodified humans.

But there’s more to it as well: a basic sense of conservation. In his Mars trilogy, Robinson introduces two opposing concepts: an aggressive push to terraform the planet (he didn’t know about the perchlorate issue then), and a reactionary movement, called the Red movement, which seeks to either stop or reverse or even just slow down the terraforming so that the original nature of Mars is not spoiled. He set up Red as a foil against the clear and obvious anarchic progress of the terraforming project, but I think there is actually something worth considering in the Red movement he talks about. Namely: why do we think it is our right or our duty to invade, infect, and destroy a pristine environment like that?

On Earth everyone bemoans when a jungle is cut down for farmland in Brazil, or when a mountaintop is removed for coal mining in West Virginia. We see that as a terrible consequence of our poor choices, and the days of reveling in the destruction of nature (by which mankind was somehow exerting his utter control) are gone with the Victorian era. Rather, we now see environmental destruction in the service of industrialized humanity as a black mark upon our planet, a horrific cost everyone wishes could be avoided somehow.

And in a real way, the desperate need some people seem to have to run away — far away to Mars, since nowhere on Earth is far enough — to escape all the problems we have here. It’s a bit of privileged silliness, especially considering how much more prevalent it is among white collar educated elites than poor people (who are happy just to move to a country that has job opportunities). Maybe, these elites think, we can avoid those horrible destructive mistakes on Mars. But we can’t, at least not with the technology we have now. Humans do not know how to move to a new space without destroying it in the process, and homogenizing it to better suit their needs. We naturally terraform our environments, even in places like Antarctica where there is an ice cream machine running in the depths of a -70C winter.

The more I learn about Mars, and the more unique and beautiful it seems, the less eager I am to plop down some inflated or buried dome for people to live on, apart from doing science in person. I don’t see the same potential for destruction on the random hunks of rock hurtling through our solar system, or even on the Moon, where the unfiltered sunlight and solar wind blasts everything clean of any possible trace of indigenous life (though even there, terrestrial microbes have survived for brief periods of time). Yes, I say colonize those for sure, mine them, use them as refueling depots — whatever. Building a dome on the Moon or hollowing out an asteroid for settlement does not seem to be as environmentally destructive as seeding Mars, unintentionally or not.

But Mars seems like the worst of all worlds: too far away to be convenient as an economic center, too toxic to live on without heavy industrialization, too massive to be an easy launchpad for other projects, and so fragile and unique that it would be a tragedy for it to be destroyed by our desire for adventure travel.

As an avowed sci-fi geek, this revelation leaves me a bit uneasy: I like the idea of space colonies even though I would never want to live in one myself, at least permanently (living in space is much harder than living on Earth). But it just seems like we aren’t ready for it, not yet anyway. We need to get much better about how to live somewhere without destroying it, and I would think the best place to do that would be here, first, on our very forgiving and very comfortable home planet. We absolutely should continue to research and explore Mars, but the idea of sending humans there so soon, while we still know so little of our ability not to ruin it in the process, fills me with no small amount of dread.