America’s Incoherent Petro-Diplomacy

Pakistan is going ahead with its natural gas pipeline to Iran, part of Islamabad’s larger project of cooperating with Tehran on energy issues. The executives in charge insist that, despite the pipeline going through restive Baluchistan, the project is nevertheless viable. The U.S. feels otherwise, and is arraying a number of hostile responses. None of them make any sense.

At a basic level, the U.S. is correct to be concerned with Pakistan’s giving Iran a huge financial lifeline through energy exports (though Iran’s supposed $500 million contribution to the new pipeline might mitigate some of that). However, that concern is not grounded. Two considerations, the pipeline’s impossibility and a lack of any credible alternatives, are lacking in U.S. rhetoric about the pipeline. The result is a confused message sparking an unnecessary diplomatic spat with a troubled ally.

CFR Senior Fellow Daniel Markey summarized all of these American concerns about the pipeline this week in a Congressional hearing.

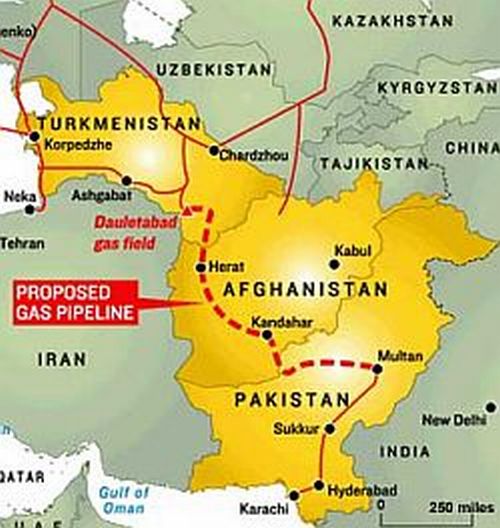

“I would suggest that while we should do everything to oppose the pipeline, including threatening sanctions should they turn it on, and including suggesting an alternative pipeline from Turkmenistan, TAPI pipeline that would probably meet their energy needs as well or better and would pose none of the problems that this Iran pipeline does pose, that that should be the packages that we go ahead with.”

This is, of course, illogical nonsense. If the pipeline is impossible to complete and won’t alleviate the very real energy considerations Pakistan’s leadership say it will… then why not just let them waste time and money and look incredibly foolish? At the same time, proposing a pipeline that must traverse Afghanistan as an alternative to crossing Baluchistan is just dumb: not only will the pipeline have to cross Baluchistan anyway (there’s no other way to come from Turkmenistan into Pakistan), southwest Afghanistan is a far more difficult, dangerous, and restive place than Baluchistan anyway. It is unserious on its face.

For its part, America has offered two tangible responses to the pipeline: sanctions, and renovating some hydroelectric dams in the country. Neither of these two suggestions deal with the driving strategic logic behind Pakistan’s decision to build with Iran:

- Legitimate, real need for additional energy supplies;

- A partner willing to contribute half a billion dollars for construction;

- Relatively low cost and short distance compared to alternatives; and

- Domestic political positioning before an historic election.

Put simply, the U.S. government’s insufficient, pouty reaction is playing into the worst stereotypes and assumptions about American motives in the region. All of the Pakistani elites who decry Washington as a bully out to keep Islamabad down and Pakistan poor can point to the hostile and unconstructive American response as evidence. Worse still, it’s not even rooted in Pakistan’s very serious terrorism problems (from the point of view of both scale and its direct support to anti-American and anti-Afghan terrorists).

The pipeline is doomed to failure. Even if it’s ever completed, Qatar, which is the region’s primary exporter and maintains a strong price monopoly on natural gas imports, will simply increase its own production to make this new pipeline economically infeasible. But this just makes the U.S. response all the more puzzling.

From a regional perspective, if the U.S. really cared about addressing this problem head on, it would do two things:

- Approach China to help further build out the Gwadar oil port; and

- Approach Qatar, which is already on friendly terms with Washington, to develop an energy import package for Pakistan;

None of these are likely to happen. For starters, China’s presence in the Indian Ocean worries U.S. strategic planners. They’d rather keep China out than give it an extra boost to solidify its already-cozy relationship with Pakistan while providing yet more economic footholds in the area.

Secondly, while the U.S. was happy to use Qatar to funnel weapons to the Libyan rebellion in 2011, those weapons quickly fell into the hands of Islamic militants. In Yemen, too, the U.S. is more frustrated than happy with Qatar’s efforts to mediate the many conflicts roiling that country. So they’re unlikely to reach out once again over Pakistan.

At the broadest, most globally strategic level, the U.S. really shouldn’t care who Pakistan ropes into its grandiose energy projects. It should care, however, about the long-term economic effects of Pakistan’s extremely patchy electrical grid; the economic and political consequences of the constant load shedding weaken the civilian government — surely the opposite of what they’d like to see happen.

By getting involved in such a counterproductive way, the U.S. is doing little more than shifting blame for Pakistan’s deplorable energy infrastructure from Islamabad to Washington. For all the world, it reminds me of Reagan’s similar brinksmanship in the early 1980s when Western Europe tried to build a natural gas pipeline from Poland. He eventually relented, the pipe got built, and nothing was really accomplished aside from some antagonism in European capitals. It was all so pointless.

American is already deeply unpopular in Pakistan. This is only making it worse. Does that matter? In the long run, who can say. But giving Pakistan a new reason to hate Washington, apart from the war in Afghanistan and the drone strikes in its northwest, seems like the worst sort of short-sighted thinking.