Keeping Drones in Context

David Remnick, editor of the New Yorker, thinks drones are just like nuclear weapons.

“We are in the same position now, with drones, that we were with nuclear weapons in 1945,” said David Remnick, editor of The New Yorker. “For the moment, we are the only ones with this technology that is going to change the morality, psychology, and strategic thinking of warfare for years to come.”

“But it’s inevitable that other countries — including countries that are hardly American allies — will follow. Then what?” he said. “We want to have it both ways: to be rid of terrorist threats without going to war in the old way, and not to have to think about the ramifications.”

There are two things here: the analogy to nuclear weapons, and the proliferation argument. Both bump up pretty hard against reality.

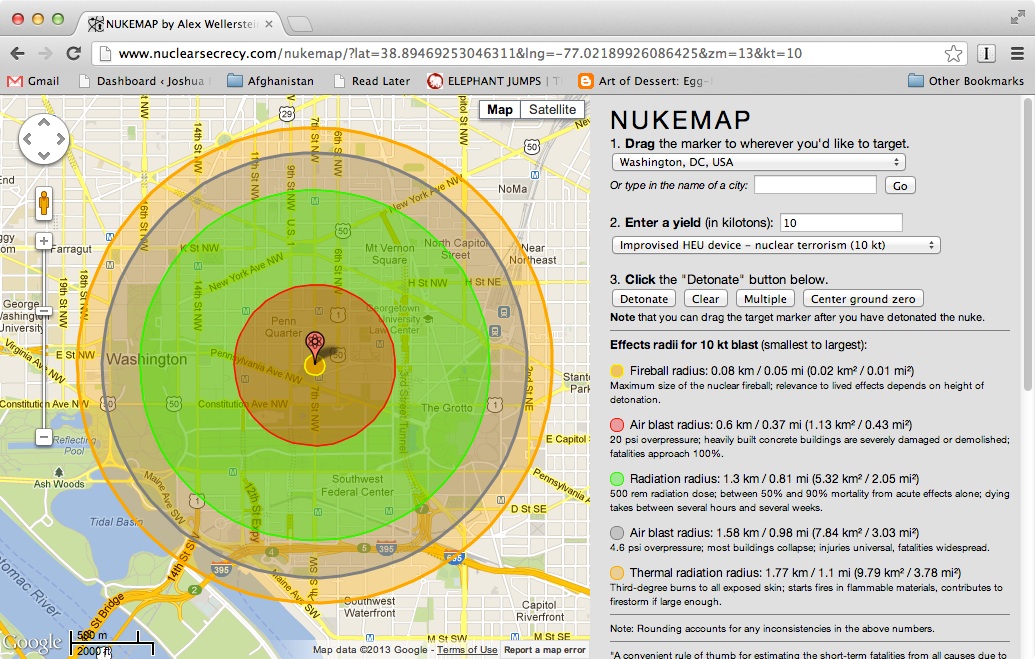

First, the nuclear weapons analogy is… curious. For starters, the reason nuclear weapons spawned their own field of study (both for effects and for counterproliferation) is because nuclear weapons cause such catastrophic, indiscriminate damage that no country can countenance their use in wartime without risking total obliteration. For example, here’s a map of a moderate-yield nuclear blast damage on Washington, DC.

A map of a small-yield nuclear device detonating in Washington, DC, from the website http://www.nuclearsecrecy.com/nukemap.

A map of a small-yield nuclear device detonating in Washington, DC, from the website http://www.nuclearsecrecy.com/nukemap.

In contrast, the Hellfire missile, which is the most commonly fired weapon from the MQ-1 Predator drone (the most common armed drone), carries 20 lbs. of explosive. More recently, the Hellfires have even been fitted with metal slugs instead of explosives — the drones are precise enough to not need a big boom to still get the person they’re targeting.

From a categorical perspective, then, the threat to people, international security, and the existence of entire societies are not threatened by drones the way they are by nuclear weapons.

Remnick then makes a different argument, which is that these weapons will seem more scary when other countries begin to use them. And this is true, to an extent: no one likes it when other powers get a hold of advanced technology. There are, however, two really big problems with this line of argument: the technology, and the politics.

First, the technology. Despite much hype to the contrary, drones are not fundamentally new technology. Even big, hundred-million dollar drones like the Global Hawk are really just aircraft fitted with radios to allow a pilot to sit outside the plane while it flies. Radio-controlled aircraft are a few decades old.

There are already shops online where you can buy the parts for a DIY drone kit and be off the ground running video feeds for only a few hundred dollars.

But that’s not how the U.S. uses drones. Again, contrary to popular perceptions, drones are rarely cheaper to buy or operate than conventional manned aircraft. For starters, while single drones are used in some limited ways for surveillance, more often they are operated in units called “orbits,” which are generally four aircraft manned around the clock to provide 24/7 coverage of a limited area. This is an expensive proposition.

According to the DOD’s Selected Acquisition Report, the MQ-1C Grey Eagle, a more modern drone than the old MQ-1, is actually more expensive to buy and to operate than an F-16 Falcon. Moreover, while it costs less to purchase than an F-35 Joint Strike Fighter, is actually requires more people and logistics to operate — making it more expensive overall.

Moreover, drones in their current state can only operate with the full consent of the host government. While it has the means to, Pakistan declines to shoot U.S. drones out of the sky (they even go out of their way to clear their airspace so the drones can operate unimpeded). Similarly, in Yemen, the government welcomes their use. Drones are slow moving aircraft without the sophisticated avionics manned aircraft have to evade detection and targeting — there’s just not as great a need when there’s no pilot on board. So unless these hostile regimes either figure out how to make even more sophisticated drones that can evade detection (an iffy prospect, since even the hyper-advanced U.S. hasn’t gotten there yet), there’s no likely scenario in the foreseeable future where drones can be used in the same way by, say, Russia.

Finally, there is the question of logistics. The average drone orbit requires around 170 people to operate in a remote base near the area where the drones will be used. This is an expensive and complex prospect involving sometimes-secret bases and a great deal of diplomatic wrangling along with military statecraft. Neither Russia nor China possess the stability or depth of relationship with host countries that would allow such an arrangement, at least not any time soon.

To summarize: drones are far less deadly, and their use far more expensive and complicated, than their critics describe. David Remnick’s concerns are certainly rooted in well-meaning skepticism of the program (and it needs a lot of skepticism), but such concerns are simply not grounded in fact. The figures I dug up here are all easily accessible on the internet — they require no access to privileged knowledge or inside access to officials to discover. It just takes some homework.

Why so many critics of the drones program do not put in the time to do this homework, whoever… well that I’ll just have to think about.