Fragility

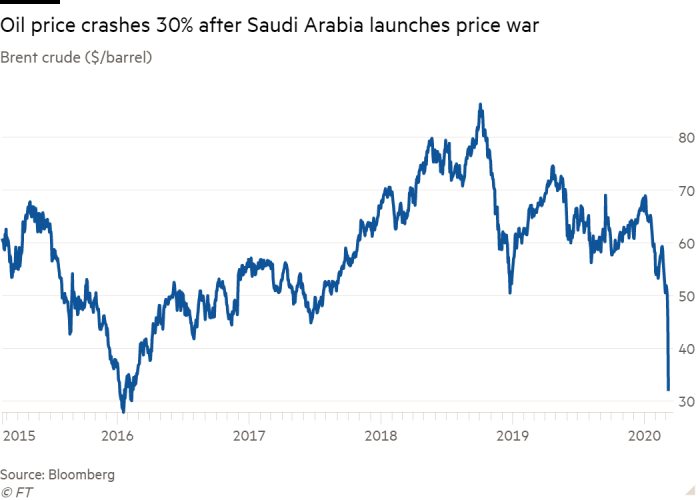

On Monday, the price of oil crashed so hard it briefly had negative value — that is, it cost more to sell it than buy it. There are many reasons for this, but a major one is that people simply aren’t using petroleum products (mostly fuel) as much while they’re stuck at home riding out the pandemic.

But supply inelasticity (whereby supply is very slow to respond to changes in the market) is, contrary to the rational economics preached by business journalists, only one part of the picture here. Nor was this a sudden blip in oil prices — since early March, the market has been wildly unstable and prone to sudden dips.

For the last six weeks or so, Saudi Arabia and Russia have been playing chicken with massive overproduction of oil, also driven by the COVID-19 pandemic. See, many huge oil consumers in Asia (China, South Korea, Japan) had issued strict social distancing rules long before anyone in the U.S. or Europe had; as a result of the sudden drop in demand, the price of oil began to fall.

Saudi Arabia saw an opportunity to edge competitors like Russia and the U.S. out of the Asian market, as the latter country had stormed the oil markets in 2014 with a massive uptick in shale oil production (which turned the U.S. into a net-exporter of energy under President Obama). So in early March, they assembled the OPEC+ consortium, which includes Russia, to coordinate a reduction in production to stabilize prices, but asked Russia to reduce its production by the largest amount. Russia refused to play ball, and instead increased its production to further drive the price down. The Saudis followed suit.

So for over a month, the biggest oil producers in the world have been churning out more oil at a faster rate than ever before, and meanwhile consumption of oil has dropped precipitously, leaving no where for all that extra oil to go. And it’s the end of a contract cycle, blah blah blah. Hence, we have a price crash into negative value. Remarkable.

Oil markets aren’t going away – as much as the world desperately needs to transition off petroleum as its primary energy and locomotive force, it isn’t ready to. And while this crash was a drastic low point, the price of oil hasn’t exactly been predictable over the last century. Even within the last year, a major attack on Saudi Arabia’s largest oil refinery (probably, but not irrefutably, by Iran) severely disrupted prices through the loss of production.

Fragility

Industry-funded propaganda aside, the oil industry is important to many classes of consumer goods, but it is not indispensable. For decades, the conventional wisdom tied the price of oil to economic health — that is, when oil prices were too high, the economy would be depressed, and when prices were low, the economy would grow rapidly. That held true for decades, but in the 2010s it stopped being true: as the recovery from the 2008 Great Recession proceeded, economic growth decoupled from oil. There are a lot of reasons for this, including the extreme inequality of the recovery, but it was nevertheless significant. You no longer need cheap oil in order to grow an economy.

Moreover, the consumer goods we rely on oil to produce — plastics — don’t need oil anymore, either, as bioplastics become sophisticated sources of carbon emissions reduction and biodegrade with fewer damaging microparticles in the environment. That’s bad for the oil industry, which has spent the last five years or so in a steady decline.

All of these weaknesses born of supply unpredictability, decoupling, and non-oil alternatives has spooked countries that rely on oil for their economies to function. In fact, there are rumors that fears over the long-term switch to electric cars and affordable large-scale renewable energy production are what’s really behind the weird Saudi-Russia price war.

That is because, far from being a stable, predictable market, oil is in fact incredibly volatile. It is fragile, when it should be resilient. And that’s a big deal.

Resilience

For several years now, the big buzz word in business “thought leadership” has resilience. You see the word plastered over the websites of mega consulting firms like McKinsey, EY, PwC, KPMG, BCG, Deloitte, Booze Allen, Accenture, Bain, and so on — you get the idea. It is the subject of extremely high dollar motivational speakers, the driver of New England business school punditry, the topic of countless leadership conferences, prominent in vendor marketing targeted at large companies, and pervasive in the executive culture of the largest firms.

And yet, much like oil, in the space of around 6 weeks the entire ecosystem of “resilient enterprises,” obsessed with succession management, crisis operations, and continuity, has collapsed into the worst economic contraction since the Great Depression. The resilience-obsessed business universe could not handle a month without revenue, and sparked a massive unemployment crisis (25 million or so, and counting) that is rapidly draining individual states of the cash reserves they built up over the last decade of recovery from the previous, also-enormous economic collapse.

The world was destined for a global recession — that is inevitable with a global pandemic with a shockingly high fatality rate. But the way an economy responds to a recession can either help it or hinder it along the way. And just as Big Oil spent the last decade passively watching popular anger and disgust at its catastrophic global impact grow, the U.S. business executive class spent the last decade chasing the grow-or-die mindset to please investors instead of building true resilience into their organizations.

It’s not like companies had no opportunity to develop resilience to let them weather a massive disruption. Analysts have been worried about a new recession for years, and there is widespread awareness of how inevitable some kind of market readjustment was.

Think of Boeing, the airplane manufacturer. The company leadership ignored employee concerns that they were cutting too many corners in their mad rush to get the 737 MAX into production, and the result was hundreds of dead innocent travelers because of a bad design that skirted FAA regulations. Just before those crashes, the company spent the record windfall afforded by Donald Trump’s billionaire’s tax break to purchasing an astonishing 73% of its free cash flow on buying stocks back from investors. Knowing markets are fragile when it comes to airline safety, knowing the economy was headed for some sort of recession, and knowing full well that the company had no margin at all should it miss revenue for very long, it chose instead to consolidate power. The CEO, Dennis Muilenberg, despite being fired by the board of directors, reportedly got a $60 million severance package anyway.

Boeing is an exemplar of why U.S. companies are so anti-resilient, but far from the only example. What drives this anti-resiliency is a culture of corporate inviolability, where workers are seen as disposable and replacement, while executives are not. It results in even cash-rich companies like Disney, with tens of billions of dollars in spare money lying around, nevertheless furloughing more than 40,000 workers due to the disruption to parks and movie production.

Disney hurting its workers isn’t a bare-knuckle financial decision by any stretch: another cash-rich company, Apple, has shut down all of its hyper-profitable stores outside of China, sounded the alarm about the economic disruptions caused by the pandemic in early February and made plans for its workforce to weather the disruption. Instead of furloughing all the hourly workers at its retail stores — because, again, those workers are responsible for shockingly high profit margins — Apple is instead continuing to pay them at their normal rate even when they can’t be on the floor selling iPhones to mall-goers. Apple is choosing to make its workforce, not just its executives, resilience.

But Apple is an exception. While some of the dozens of companies throwing people into unemployment were never particularly healthy (JC Penny, Tesla), plenty of huge, profitable, growing companies (Under Armor, Marriott) are also hurting workers. Either their growth numbers were juiced to keep their stocks artificially high (as Tesla CEO Elon Musk seems to do), or the entire idea of “resilience” is a big joke, a fig leaf barely covering executive cowardice and short-sightedness.

Guess Who Loses

All the hue and cry about resilience and the country’s largest companies barely lasted a month without their usual revenue. Say what you will about oil, but the constant market instability means the big petro companies are a little bit better at weathering price disruptions (one of many reasons Monday’s price crash was interesting, but not very significant).

The challenge facing the U.S. is that the government is not very resilient, either. As George Packer argues convincingly in The Atlantic, the U.S. government has been attacked for decades to reduce its capacity to regulate economic shocks and help the neediest of society.

Trump acquired a federal government crippled by years of right-wing ideological assault, politicization by both parties, and steady defunding. He set about finishing off the job and destroying the professional civil service. He drove out some of the most talented and experienced career officials, left essential positions unfilled, and installed loyalists as commissars over the cowed survivors, with one purpose: to serve his own interests. His major legislative accomplishment, one of the largest tax cuts in history, sent hundreds of billions of dollars to corporations and the rich. The beneficiaries flocked to patronize his resorts and line his reelection pockets. If lying was his means for using power, corruption was his end.

This was the American landscape that lay open to the virus: in prosperous cities, a class of globally connected desk workers dependent on a class of precarious and invisible service workers; in the countryside, decaying communities in revolt against the modern world; on social media, mutual hatred and endless vituperation among different camps; in the economy, even with full employment, a large and growing gap between triumphant capital and beleaguered labor; in Washington, an empty government led by a con man and his intellectually bankrupt party; around the country, a mood of cynical exhaustion, with no vision of a shared identity or future.

So.. that’s great. And it’s where we land with a hilariously inadequate “stimulus” package that cost $2 trillion but barely covers a single week’s worth of the average family’s income, that is already being siphoned away by the large companies that mismanaged their way into massive layoffs.

This isn’t a resilient system. It is a declining system. And this didn’t touch on the largest sector of the economy — healthcare — which was its own nightmare of anti-resiliency before the pandemic made hospitals back up with refrigerated body trucks.

Far from being the most flexible, adaptable society facing a major threat, America in 2020 has turned out to be venal, short-sighted, and fragile. This isn’t greatness under any definition, and absent something truly dramatic happening, I’m not sure why we should expect anything to get better anytime soon.