Videogames and Security Politics

Very loosely adapted from a guest lecture I gave on May 14, 2023, at the University of Melbourne.

My PhD research is about videogames and politics – specifically, how the US military uses gaming in its various forms to drive strategic communication processes. This means I am working off the assumption that videogames are a) serious (which is not the same as “serious games” – more on that in the future); b) political (in the sense that they have politics); and c) not fully appreciated as either in either policy or scholarly circles.

So, let’s do a quick overview of how I am viewing the interplay of games and politics, which will both help me organize some of my own thoughts and hopefully provide a roadmap for others to get inspired to do their own investigations.

Hate

The most common physical stereotype of a “gamer” is a young white man sitting alone in a darkened room, his ears fully ensconsed in a pair of noise cancelling headphones, eyes rapt on a bright screen. The most common social stereotype of a gamer is a young white man who freely uses racial and sexual epithets to belittle and demean anyone who does not look like him, both while playing a game and in online spaces when he isn’t.

There is, as with all stereotypes, an element of truth to this. But it isn’t entirely accurate.

In the image above, taken from the Entertainment Software Association’s 2022 Essential Fact guide, 48% of gamers identify as female and nearly 2/3 of the US play games regularly. The stereotypes of the angry, hate-filled male gamer are out there, but they are not the typical person who engages with games.

This has two implications. First, many researchers who are not specialized in games research have a default assumption there is something inherent to the games that cultivates extremism, like white nationalism, violent and/or incel misogyny, or various forms of anti-semitism and racism. A recent study by ISD into the ways extremism is socialized and expressed in videogame forums found, instead, that there is “limited evidence to suggest that online gaming is used as part of a deliberate strategy to groom new people into extremist movements.” In other words, while extremism certainly exists in these spaces, and has sometimes violent expression, it is not an intentional choice by either the game makers or even by extremist movements.

So, there is something else going on that we should look at if we’re to understand the intersection of videogames and politics.

The Extraludic Community

The scholar Sky LaRell Anderson, an Assistant Professor of Digital Media Arts at the University of St. Thomas in Minnesota, coined the term extraludic communities to describe the type of social environment that springs up between people who enjoy playing games, but which takes place and often engages in discussion about things outside the game itself.

These are the communities ISD found extremism in its study – not necessarily within the games themselves, but in communities that initially organized around those games. The recent national security leaks by Jack Teixeira took place in one of these communities: a Discord server ostensibly about gaming that also served up piles of anti-semitism, violent misogyny, anti-Black racism, homophobia, white nationalism, and, of course, volumes of sensitive national security information.

These communities serve as a way for gamers to organize themselves, though they are not necessarily places where those organized groups mobilize for action. Rather, the act of coming together seems to work more as a source of empowerment and agency for the men who join, even when it also results in their directing abuse toward outsiders.

Implications: Propaganda and Strategic Communication

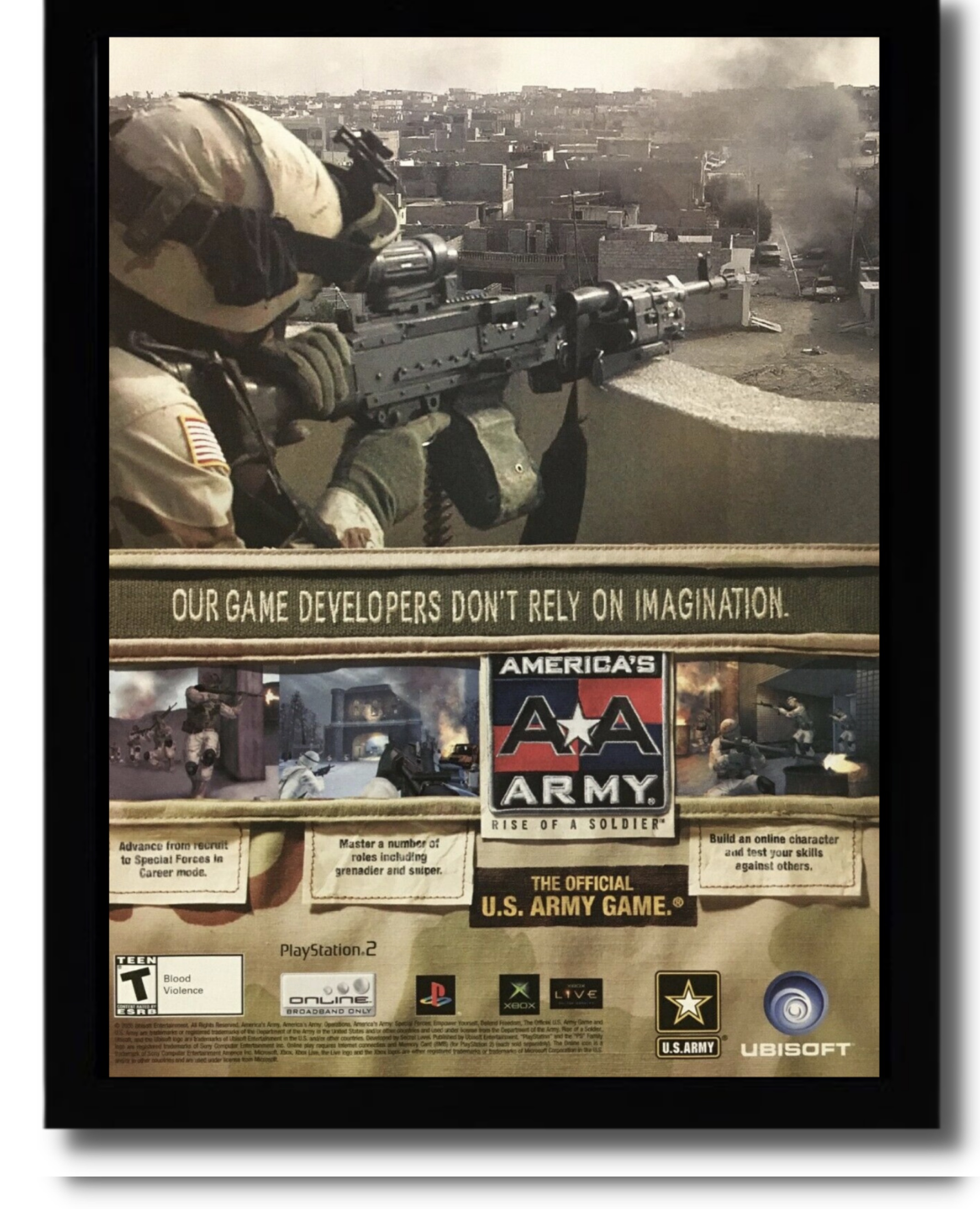

Many governments and non-state actors have taken notice of the way these extraludic communities can operate in a political context. The US Army was arguably the first to do so when it launched the America’s Army videogame back in 2002. Initially envisioned as a recruitment drive (though there is no indication it actually grew recruitment since it launched at the same time as a nationwide rally-round-the-flag effect was operating after the 9/11 terror attacks), AA was meant to provide a realistic portrayal of military service. It didn’t really do this – the guns were realistic, sort of, but player movement, combat, violence, and rear echelon life were not remotely realistically portrayed. Still, the army marketed it as an experience where players do not need to use their imagination.

A major concern raised by media commentators at the launch of this game was its obvious propagandistic intent: by sanitizing the experience of combat while claiming to make it realistic, and portraying the US as generally light-skinned good guys killing generally dark-skinned bad guys, so the critique went, it was instructing Americans to adopt a neoconservative view of the still-new War on Terror. Moreover, since it was a recruitment tool, it was necessarily aimed at teenagers – the army’s primary pool for new recruits are people just graduating from high school.

While these are valid concerns, in hindsight it is worth asking if any of it really came to fruition. After all, by 2008 the army was continuously lowering recruitment standards because it could not make its quotas to meet its mission needs, and at the same time Americans had turned sour on the wars in both Iraq and Afghanistan, leading to a wave of Democrats winning office based on opposition to forever wars. If this was such dangerous propaganda, surely it would have had an effect? That does not excuse the attempt, but it worth keeping in mind that these are not straightforward processes.

Despite the lack of proven effectiveness, other militaries and militant groups have been trying to use games for strategic communication. Here, you can see a small sampling. Counterclockwise, from top-right: “Glorious Mission,” inspired by America’s Army for the Chinese People’s Liberation Army; “Holy Defense,” by Hezbollah’s media arm to let people kill ISIS militants; “Save the Freedom,” by the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps to let players rescue George Floyd from the Minneapolis police; and “Liferun,” a special zone within Fortnite designed by the Red Cross to teach international humanitarian law.

Effects Are Hard

Do any of these games “work?” Or, more specifically, what do games do?

Like with America’s Army, it can be hard to say, but there is no real indication yet that these games necessarily persuade people to change their beliefs. Media effects are hard to measure, and many popular conceptions of how effects work rely on an obsolete hypodermic needle or magic bullet model – one that assumes audiences are passive, that messages have consistent and predictable effects, and that these effects happen in discrete units that can be qualitatively measured. That does not mean these messages have zero effect, despite the hype from Big Data industries that want to market new PR widgets.

More sophisticated theories of how media can act persuasively on audiences, from agenda setting to framing to cultivation theory, assume a more complicated process. Agenda setting argues that the way media presents topics as salient to an audience prompts them to consider those topics as salient – that is, if thing A appears in the news, but thing B doesn’t, then the audience will assume thing A matters more than thing B. Framing takes this a step further, and argues that the way in which those topics are portrayed can shape how audiences view the menu of possibilities they can then believe about it – so, when the political press presents a liberal welfare policy proposal but only talks about it in terms of immediate cost and tax increases, the audience will tend to view it as overly expensive regardless of long term or social benefits. Cultivation takes a longer term view to argue that the cumulative effect of media exposure to a set of ideas can, over the long term and through repeat exposure, shape or influence a person’s belief system to conform to the nature of that exposure.

All of these are intriguing and offer some tantalizing clues about what these various uses of videogames for strategic communication might be doing to society – after all, far more people play a similar set of videogames than watch a similar set of TV shows, read the same news sources, or listen to the same radio shows. I am arguing in my dissertation that videogames are the new global public sphere, and need to be treated as a form of mass media with the potential to persuade and shape public discourse as much as television was in the 1960s and 1970s.

But actually researching this is difficult, as it requires intimate access to a person’s thought process, history, influences, needs, preferences, and long term behavior. It isn’t impossible, but it takes a lot of work, and the demands of academic publishing make such studies extremely rare.

GamerGate as a Prototype

Arguably the clearest way we can see the interplay between videogames and global politics is GamerGate. It began as a bad break up between a female game developer and her boyfriend, where he wrote a lengthy screed about their relationship that then went viral and inspired a wave of harassment and abuse directed against women in the industry. While it began organically, it was quickly coopted and amplified by right wing media figures. They were primed to do this because of one figure in particular, who, a decade earlier, realized something about how men in particular related to gaming.

In 2005, Steven Bannon — an important adviser to Pres. Donald Trump and funded by right wing billionaires in the US — build a company around farming assets in the multiplayer game World of Warcraft, which he would then sell for real world currency. The business itself went nowhere for a variety of reasons (margins were too slim, Blizzard changed the way the game economy worked, etc.), but he told a journalist that the experience trying to market this company to gamers in the US showed him that young men online have “monster power.”

After GamerGate began chasing women and queer people from their homes through a barrage of rape, death, and bombing threats, the political website Bannon managed at the time, Brietbart, dedicated wall-to-wall coverage to amplifying abuse and defending the most vocal abusers. They did so through a culture war lens, alleging that “liberals” and “feminists” wanted to “take away your games” (a reference to the assumed default white male gamer) by broadening the type of person represented in game design.

This is a huge topics still subject to contentious discussion online (and if anyone who still supports the harassment campaign reads this, they will probably direct hate at me for even mentioning it), but the big takeaway from the scandal is that it normalized violent harassment online, acting as a sort of think tank for internet-based abuse.

Crucially, Bannon saw a way to mobilize young men through videogame themed culture war tropes, and key figures in the movement shifted seamlessly from attacking women in the industry to campaigning for Donald Trump in 2016. It has become an article of faith with technology journalists that that “Gamergate’s DNA is everywhere on the internet.” You can link the current rise of a transnational far-right authoritarian movement in English speaking countries directly to this scandal.

A Jumping Off Point

So, this is my jumping off point: videogames are culturally dominant. They are being used by powerful, global actors to engage in persuasion. The people who play them have been mobilized and coopted to engage in violent hate campaigns. They have shaped political outcomes. And we aren’t really sure how they do this.

Sounds like a neat jumping off point for research, no? I certainly think so. Stay tuned for more – I’ll document bits and pieces of this phenomena as I continue my research over the next year, and hopefully we can all come away a lot smarter.