The Whiteness of Outdoor Brands

This is a follow up to previous posts on diversity in the outdoors. See previous entries here and here.

Last year, in the midst of the protests for black lives, the professional cyclist Ayesha McGowan wrote in Outside magazine about the challenges of being black in the outdoor industry. “I distinctly remember being a young adult looking at the window displays of large outdoor retailers,” she wrote, “and wishing there was even a touch of representation for people of color.” I take her comments to heart: representation in outdoor brands, and the industry as a whole, seems to be extremely lopsided.

This is an important conversation to have for two reasons. First, the ways in which the outdoor industry represents itself has serious implications for both the economy and culture — according to the Bureau of Economic Analysis, Outdoor Recreation accounts for nearly 2% of the U.S.’s GDP, around $460 billion each year. This makes it larger than agriculture ($454 billion) and mining, oil & gas ($419.9 billion). Just by nature of being so large, the way in which the outdoors industry presents itself is meaningful to the economy.

The second reason this is an important conversation is because — despite the toxic politics invented by racist agitators — representation still matters. Research shows that when media images of one type of person dominate a field, people who don’t fit that image feel like an Other — precisely what McGowan talked about in her Outside article. Really fascinating research in neuroeconomics shows how this can play out physiologically: some brands can mobilize marketing to trigger neural pathways associated with “self-centered cognition,” meaning an ad can active through patterns about how you envision yourself and relate yourself to others.

Bruce Berger once noted that public relations is, in many ways, “an attempt to construct ideological world view.” Organizations use the images and words they publish to “shaping social and cultural values and beliefs in order to legitimise certain interests over others,” as Lee Edwards and Caroline Hodges put it.. In other words, things like marketing, public statements, and corporate representation are an ideology, even if the organization doesn’t consciously realize that’s what they’re doing (we subconsciously amplify our ideologies all the time).

Representation in public relations demonstrates how an organization perceives its primary stakeholders and interest groups — they represent the people to show up in statements that they consider most salient to their interests, whether its an advertising, an internal memo, the characters in a catalogue, and the spokesperson they choose to speak to the media.

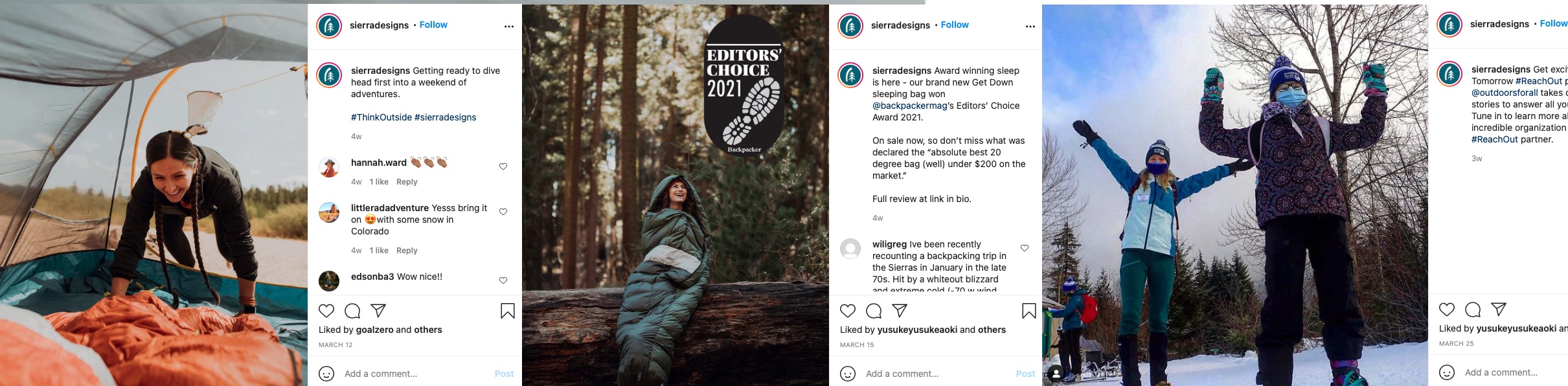

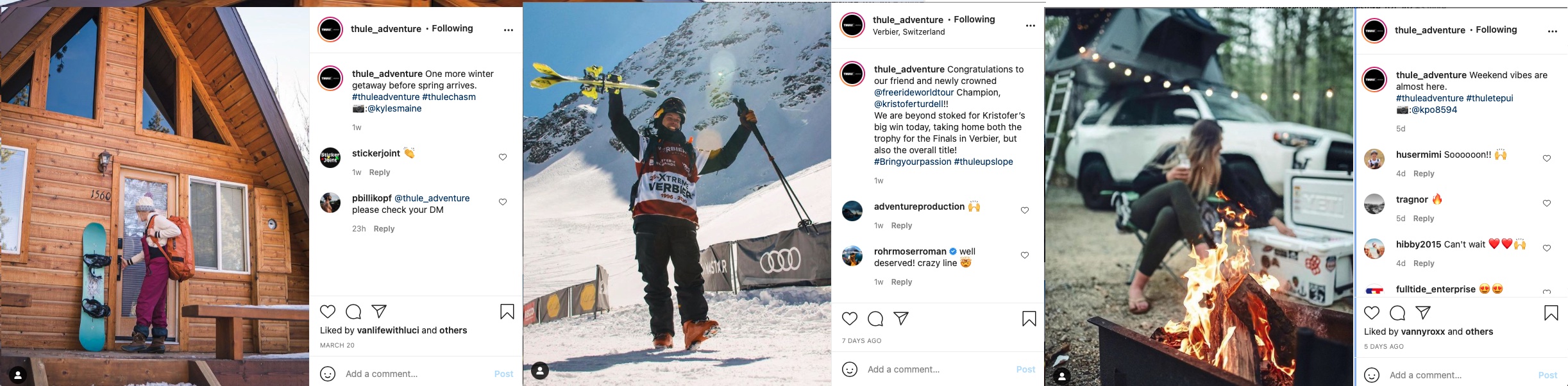

So, to follow up with McGowan’s experience not seeing any people of color in marketing materials at the outdoor stores where she shopped, I wanted to see how outdoor brands represent themselves online. What worldview are they constructing with their model choices? I picked a few mainstream brands that are well-known in the backpacking community — NEMO, Thule, Osprey, and Sierra Designs — and looked at series of 5 recent Instagram posts, bounded to the month of March, 2021, to see what sort of lessons we can learn about representation.

I want to be clear, when I talk about representation on Instagram, am not calling out these companies specifically. They are exemplars, and they don’t seem to be particular outliers compared to their competitors. So while this is not an empirical determination of representativeness, I do think they broadly show the mainstream of the industry.

There’s also a danger of doing a “representation audit” this way, especially given my own status as a white (gay) man, since not all representation is perfectly visible. So, it is possible I missed something, and I want to emphasize that this is cursory — that is, I am not doing a deep dive here, it’s just an exercise that’s interesting to me, based on some intriguing theory about public relations. Moreover, many reactions to representation are actually based on a cursory view; it’s one reason commercials have only recently moved away (a little bit, at times) from highly exaggerated stereotypes of people hawking products.

So, this isn’t science here, it’s just a blogpost where I’m exploring an analysis technique, looking at the text of a small number of Instagram posts from a small number of brands. But even so, I think it results in something interesting that I want to follow up on.

I won’t post all of the images (apologies for the misaligned stitching), but looking at these 20 posts there are very clear trends:

- Representation in these brands is highly unequal. The only obvious person of color in the posts is an out-of-focus Nepalese woman, taken from a still frame of a documentary Osprey sponsored. While Osprey featured exclusively women, Thule and NEMO feature more men than women. Otherwise, everyone appears to be white, to an alarming degree

- The nature of the representation matters. As an example, while NEMO used a woman to illustrate a post advertising a recliner chair, the model was not tagged. Her male photographer, however, was. This holds true for Thule, as well, which features a female snowboarder but credits the male photographer. This is not consistent, however: in another Thule post, the professional triathlete Sarah Stan Crowley is named and credited along with her male photographer. This is perhaps a weakness of influencer marketing, where attribution is not always clear.

- Osprey’s posts feature exclusively women in its imagery, all of whom are wearing backpacks in remote-seeming outdoor locations. Three of the posts include dogs, one includes children, and one has a person of color. In every post, the subject’s back is facing the camera so as to highlight the backpack; this also has the result of depersonalizing her.

There’s obviously a lot more that can be read here; it’s probably a critical analysis article if I ever have the time to write it. But I’m struck by how Ayesha McGowan’s childhood angst at not seeing anyone who looks like her in the outdoor retailers seems to be continued by the brands examined here. While the prevalence of women is noteworthy — Cheryl Strayed wrote in her 2012 memoir Wild that she saw almost no other women during her thru-hike up of the PCT 1995 — women are still not represented equally to men in the total set of brand imagery, though individual brands (like Osprey) make it a point to show women in active settings.

I was also struck by how unequal attribution showed up in the imagery. Male influencers or photographers are credited meticulously, but female models or athletes are not. This probably merits further investigation, too.

What else can we learn from this? The outdoors remains an ideologically very white space, and it doesn’t seem to be intentional — I suspect there is a steep imbalance in the racial makeup of outdoors influencers, which is worth contrasting with accounts like Brown People Camping, which try to emphasize the “available to all” aspect of outdoor recreation. And there are other groups trying to diversify how we think of the outdoors, like LatinxHikers. These groups are doing heroic work to correct the racial imbalance in the outdoors industry, but they have a lot of work to do, and they shouldn’t be laboring alone.

But in the end, despite progress on the gender front, the marketing of the outdoors remains a very white space. Considering the huge size of the outdoor economy, such a steep racial imbalance has not only social implications (I love the outdoors, and the idea of someone feeling unwelcome to it because of their skin color is upsetting), but economic as well. Efforts to quantify the economic cost of racism in Hollywood showed it costs that industry billions of dollars per year; what are outdoor companies missing out on by excluding people of color, however unintentionally?

This is a rich vein of future research to explore further, and hopefully I’ll have the chance to do so over the next couple of years. Racial disparities in corporate representation is both expensive and socially impoverishing — it makes all of us worse off. But we still don’t really know how to think about it in an active way. It’s a huge problem.