Our Broken National Security Politics

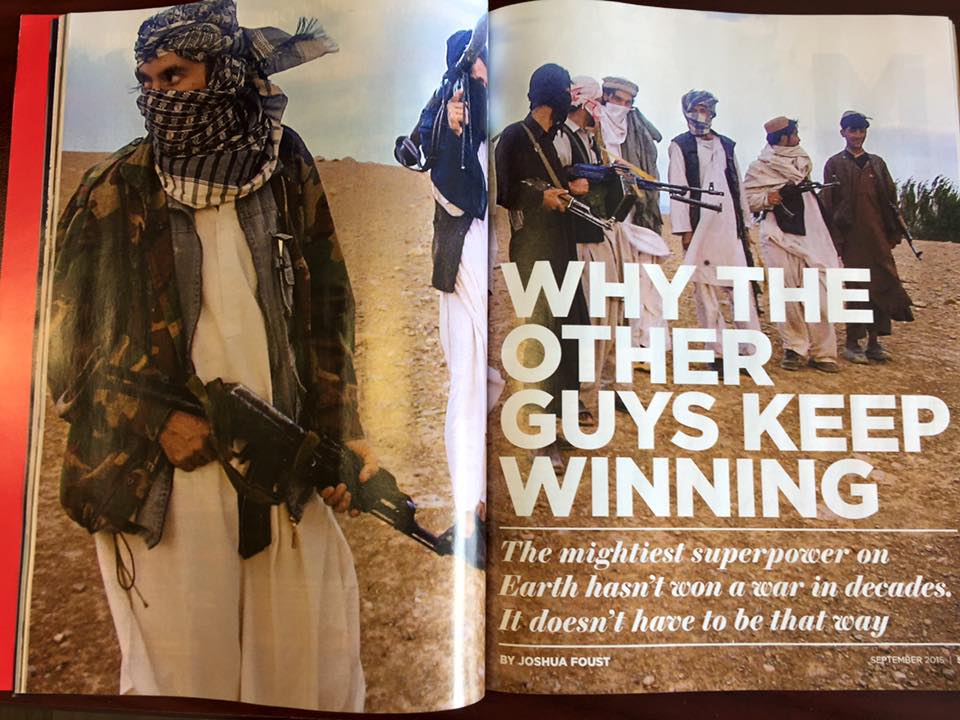

I have a longform piece in the September, 2015 issue of Playboy. It isn’t online yet, but you can see the spread below: It is online! Go read the whole text here.

If there was a main point, it is this: “the politics of America’s wars have failed. The military can do combat just fine, but the politics of war that give the military scope and direction have fundamentally broken down.” In the article I explain, in detail, how that has occurred and what kind of decisions and policies that ends up creating.

One of the key takeaways I got from researching and writing this was how outdated the idea of victory is. It just doesn’t seem relevant. But related to that is a tendency I’m sure we have all noticed at varying times in the past: the fact that war mongers — that is, people who blindly demand more war, regardless of the context — are richly rewarded with access, privileges, speaking gigs, TV appearances, op-ed space, and think tank fellowships. Those who advocate for less war, or who are skeptical of the transformative power of American military force, are often punished professionally for their ideas. The game is rigged pretty explicitly.

Unfortunately, threat inflation is a fact of life that isn’t going away any time soon. The action bias of national security punditry is here to say, because people prefer action over inaction, even if our own experiences really say that that is a destructive instinct.

Nor is the rejection of specialist knowledge going away, either — way back long ago, I covered just how deliberately almost every actor, from academics to think tank pundits to journalists to the Pentagon to the White House, excluded actual experts on Afghanistan from their advocacy about the war. No one cared what the reality was because they had their ideologies — whatever they were! — to promote.

At the same time, the personality cult of generalship also badly distorted things. The way Stanley McChrystal organized a whisper campaign to fire David McKiernan was nothing short of disgraceful, but the journalists who covered him never bothered to question what had happened, even when McChrystal’s new plan was basically the same as McKiernan’s, only with more money attached to it. People whose careers depend on their closeness to McChrystal insist that it was different, unique, effective, and so on — but on the facts, on the actual policy and operational realities that came from it, it was not. But the myth endured.

You can see that myth on display now, as people wonder how on earth we are supposed to solve ISIS. David Petraeus pleaded guilty to handing classified materials to his mistress (who lied profligately in her book-length love letter to him), yet he is still vetted by the White House for his expertise on the region he is materially responsible for ruining. The power of his personality cult outweighs anyone’s common sense about whether the effects he created in Iraq were appropriate at the time (they were not), and whether they could be repeated now (they cannot). It’s celebrity worship.

At the same time, David Petraeus is a relentless advocate of expansionist American militarism, regardless of location. He publishes op-eds calling for more troops, more time, more lives, more money, with Michael O’Hanlon (who I highlight in Playboy as exemplifying the destructive DC mindset of worshipping the military, and whose skill at the DC military-fluffing game is legendary). No one seems to care, they just love his decisiveness.

Despite a record stretching more than a decade of being consistently wrong on the facts, being wrong in analysis, and making bad predictions, war boosters like O’Hanlon (or Max Boot) have only become more entrenched in their senior positions at powerful think tanks. Their actual performance is immaterial; what matters is that they are friends with the politically popular generals who have also been horrifyingly wrong about the wars.

So I come out of writing this Playboy essay rather depressed about the state of national security politicking. I think it is broken in some fundamental way, where down is up and failure is success so long as everyone thinks hard enough to make it so. And I don’t really know what to do, outside of some things at the margins.

I don’t know, maybe that’s just part and parcel of the broader issue in our society as well: we all seem to know, at various levels of instinct and direct cognition, that something has gone sideways in some way — that our system of rules, norms, and values has slipped off the rails at some point. But I am at a loss for how we can fix them. Maybe some of you can generate some ideas.